There is one big caveat to all the realizations about how to control our reactions to frustrating situations. You can understand as much as you want and be as zen as you want; yet, you can still have such a bad day that you blow up anyway.

Of course bad days happen everywhere. The difference is that everything we normally do to control those is no longer available. We cannot ignore everyone and walk down the street listening to music. Even when I am in Gabs, I run into people I know all the time. We cannot go to our favorite bar and spend time with friends. We cannot call people and talk for hours, take a spur-of-the-moment trip if we need to get away, or really show anger at all.

We do not have our normal support systems. And although it is said often, its impact is immeasurable.

We are never OFF as Peace Corps Volunteers. We have been known to hide in our houses when people knock on the door because we can't deal with seeing anyone at that moment. Maybe we were watching TV. Maybe we were stuffing fudge into our mouths. Or maybe we were just crying. We used to be able to feel "alone" even in public, like sitting at a cafe drinking coffee and reading. That is gone. We can't walk to the grocery store and be anonymous.

I also know that we chose to do Peace Corps. We chose to put ourselves through this challenge.

Nevertheless, the caveat to self-control is that sometimes it just goes out the window. Sometimes our emotions and our frustrations get the best of us. And no matter how often we try to control it, sometimes it's not possible. And I have found that the emotional fallout from this is greater than it would have been if we were home.

The opinions expressed in this blog are mine, and mine alone. They do not represent the views of the Peace Corps or the United States Government.

Wednesday, June 20, 2012

Tuesday, June 19, 2012

One Year

During training, many volunteers came to lead sessions. They helped us with everything--how to purchase internet, how to navigate the buses, cultural issues...you name it, we were able to ask them. One thing we continued to hear was that it really takes one year to feel comfortable enough in your village in order to start doing some real work. It takes that long for people to trust you, to know what you are there to do, and to want to work with you.

The "one year left" mark brings with it many reflections for me, in no particular order:

1. At some point soon, I will have to start thinking about what I want to do after Peace Corps. That got me thinking about how to represent this experience on a resume (a daunting task). In thinking about this, I wondered what I would say if someone asked me the biggest thing I learned from Peace Corps. So here is my current answer: everything you think you know about the world can be challenged if you truly understand it from someone else's perspective.

2. There is no real way to accurately describe this experience to someone who has not gone through it. Obviously my fellow Botswana PCVs understand it better than most, but the majority of the time I am in my village alone. This journey is uniquely mine and no one will be able to claim they have done exactly what I have.

3. There are many things we hear about PC service before we leave the states. One of the most widely used quotes about PC is, "It's the toughest job you'll ever love." Generally, I dislike clichés. That being said, it is remarkable how much we can simultaneously love an experience that makes us cry, scream, feel alone, insecure and insignificant.

4. As humans, there are going to be times when we are unhappy. To put it bluntly, we are going to get pissed off. There is no way around it. But we can lessen the frequency and severity of those instances by controlling our reaction to them. Instead of being pissed off that no one came on time to a meeting, we can bring a book while we wait. We will then be available whenever people decide to show up. We can understand that people don't mean to offend us when asking us for money or calling us "lekgoa." We can know, no matter how many people we ask not to do this, that it will continue to happen. Accepting the way things are can save us a lot of headache and hassle. I like to explain it this way:

I don't necessarily think it takes a full year to start doing things in our villages. By this point, people in my group have started community gardens, taught Life Skills classes, planned Girls Leading Our World (GLOW) camps for girl empowerment, taught basketball, advocated for the rights of people with disabilities...just to name a few. But for me, there is an ease of living that has developed over the past month. I don't feel like I need to force anything. I no longer have an idea of what I "should" do. I know what people in my community want to work on and I am ready to support them in their endeavors.

The "one year left" mark brings with it many reflections for me, in no particular order:

1. At some point soon, I will have to start thinking about what I want to do after Peace Corps. That got me thinking about how to represent this experience on a resume (a daunting task). In thinking about this, I wondered what I would say if someone asked me the biggest thing I learned from Peace Corps. So here is my current answer: everything you think you know about the world can be challenged if you truly understand it from someone else's perspective.

2. There is no real way to accurately describe this experience to someone who has not gone through it. Obviously my fellow Botswana PCVs understand it better than most, but the majority of the time I am in my village alone. This journey is uniquely mine and no one will be able to claim they have done exactly what I have.

3. There are many things we hear about PC service before we leave the states. One of the most widely used quotes about PC is, "It's the toughest job you'll ever love." Generally, I dislike clichés. That being said, it is remarkable how much we can simultaneously love an experience that makes us cry, scream, feel alone, insecure and insignificant.

4. As humans, there are going to be times when we are unhappy. To put it bluntly, we are going to get pissed off. There is no way around it. But we can lessen the frequency and severity of those instances by controlling our reaction to them. Instead of being pissed off that no one came on time to a meeting, we can bring a book while we wait. We will then be available whenever people decide to show up. We can understand that people don't mean to offend us when asking us for money or calling us "lekgoa." We can know, no matter how many people we ask not to do this, that it will continue to happen. Accepting the way things are can save us a lot of headache and hassle. I like to explain it this way:

Unhappiness does not come from the way things are,

But rather from our wish that they were otherwise.

5. There is something to be said for contentment. Contentment does not mean that one is not looking for better opportunities and improvements in one's life. Contentment means that one does not need external validations to be happy. Americans were raised knowing that we have the right to "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." Ironically, the pursuit of happiness seems to be the source of all unhappiness. Too often, we feel the need to reach a certain point in our lives, by which we think we will be happy...a job, a marriage. We want our life to look a certain way. That means happiness. I refuse to live like this. The destination of the journey of life is death, so I am going to enjoy the journey.

I don't necessarily think it takes a full year to start doing things in our villages. By this point, people in my group have started community gardens, taught Life Skills classes, planned Girls Leading Our World (GLOW) camps for girl empowerment, taught basketball, advocated for the rights of people with disabilities...just to name a few. But for me, there is an ease of living that has developed over the past month. I don't feel like I need to force anything. I no longer have an idea of what I "should" do. I know what people in my community want to work on and I am ready to support them in their endeavors.

Monday, June 18, 2012

Mini Vacation II: Machaneng and Tuli Block

Each new group of trainees gets to shadow a currently-serving volunteer during Pre-Service Training. They spend a week with us, learning about our job and how we integrate into our community. I have been blessed with two amazing shadowees, Celia and Tate. Celia visited me last November (see previous posts here and here). Tate came in May of this year.

Tate and I had a great week. She saw the clinic, helped me begin my Life Skills class and held a focus group with a bunch of my friends in Shoshong. Celia and I did a focus group with junior secondary school kids (ages 13-16) so I wanted Tate to meet a new group. I got together some of my out-of-school youth friends, aged 24-34. She spoke with them about their hopes and fears about the future. It was really interesting. They urged us to work on supporting the youth with businesses rather than simply teaching about HIV/AIDS. Two even said that HIV isn't a problem here and we should focus on other things. Definitely gave Tate a lot to think about as she begins her work.

And then we traveled to Machaneng to visit the volunteer there, Stephanie. We spent a night out on the Tuli Block, an area in northeastern Botswana known for its extensive family-owned farms. During her service, Steph became close with a family who lives on a farm right outside of Machaneng. They invited us out to see the area and the animals. We had a great time.

|

| Tate and I |

|

| The group that went to the Tuli Block, from left: Matt, me, Leah, Chad, Tate and Steph |

|

| As Steph's friend drove us through the farm, we were able to see the thousands of acres of African bush. It is beautiful. Here I am standing in front of the Limpopo River. |

|

| And we saw giraffes! |

|

| They had a Caltex gas station on the property. I thought this was pretty funny. |

Wednesday, June 6, 2012

Untitled

The enjoyment of watching our favorite shows doesn’t always

stop when we come to Peace Corps.

Oftentimes we get hooked on new ones.

We live alone and there’s only so much reading and playing solitaire one can do

on a Saturday night. My current show of

choice is The West Wing.

Season 3 Episode 1 aired right after September 11th,

so they deviated from the normal storyline and shot a completely different

episode. In it, many members of Senior

White House staff talk with a group of high school students about Islamic

extremism. The students ask the main question

many of us were asking at that time: why do they hate us so much? During the conversation, the White House

Communications Director tells a story from his childhood, evoking the Holocaust. It really struck me.

“A friend of my dad’s was at one of the camps. He used to come over the house and he and my

dad used to shoot some pinochle. He said

he once saw a guy at the camp kneeling and praying.

He said, ‘What are you doing?’

The guy said he was thanking God. And my dad’s friend said, ‘What could you

possibly be thanking God for?’

He said, ‘I’m thanking God for not making me like them.’”

Somehow having the grace to maintain my humanity at a time

like that? I’d thank God too.

...Thoughts?

Sunday, June 3, 2012

SINGLE. WHITE. FEMALE.

Brene Brown, a social worker/researcher, presented her

findings as a TED Talk a couple years ago.

She began by trying to understand shame.

This preliminary question led her to life changing research about the

nature of our vulnerability. Brown says

that shame is caused by the fear of not being accepted. We all yearn to feel belonging.

Therefore, we create groups, microcosms based upon common

characteristics. By defining ourselves

in certain ways, inherently the “other” is created. That is the first step to stereotyping and

discrimination. We can create clubs

based on income, interests, shared experiences, etc. But the most common groups are created based

on the most obvious differences between us: physical characteristics. Race.

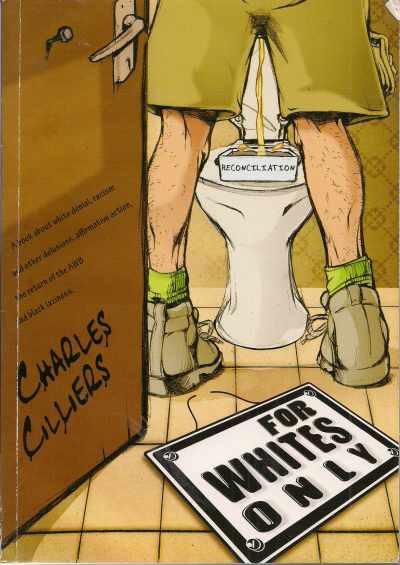

In the Peace Corps office, we have a whole shelf of old

books volunteers leave when they return to the states. There are enough books to keep all of us busy

reading for months. On my last trip

there, I picked up a book called “For Whites Only” by Charles Cilliers. It looked thought provoking (see cover below)

so I took it. I have about 10 books

sitting in stacks in my house, but I decided to read this one. Boy, I am glad I did.

The book is about race in South Africa (see my first post

about this here). Cilliers is a white

South African. He wrote the book for

other white South Africans, to make “us more open and willing to learn, as well

as appreciative of the many white people who took a stand against apartheid and

racism and helped to pave the way to democracy.” I am not quite done with it, but will still

wholeheartedly recommend it for ANYONE to read—any race, any nationality. I read it particularly to draw parallels with

race relations in America.

Lately, I have found myself comparing Americans and

Batswana—not in a judgmental way per se, but more to just process the views

engrained in me as part of my culture.

But I began to wonder if I was generalizing too much, lumping all

Americans into my America as a white, middle-class female. That being said, I grew up going to inner

city Providence all the time. My dad

worked at a high school there. My mom

tried to open up a multicultural center while serving as an AmeriCorps

volunteer in the south right after the assassination of Martin Luther King,

Jr. Needless to say, my parents were

always inclusive of everyone. I was

never raised with any notion to think of someone differently because of the

color of their skin. But I still lived

in a predominantly white area and attended predominantly white schools. I cannot deny that being Caucasian is part of

my identity. Regardless of how we define

ourselves—by the color of our skin or not—the world has a tendency to do so

anyway.

You will oftentimes hear volunteers here say, “Batswana are

like this….Batswana are like that.”

There are lazy people here for sure.

There are also incredibly hardworking people. Same as in the states. One thing Cillier’s book challenges is that

race has anything to do with laziness/ambition/kindness etc. If I grew up in Botswana, white or not, I would

be a Motswana woman and view the world as they do. Europeans were not inherently smarter or more

progressive than Africans. They just grew

up in different environment, especially in terms of the availability of land,

and were shaped differently.

Most Batswana are Christians, owing to the influence of

European missionaries in the 1800s.

Traditional healers do exist, but they are much less common than before

the European influence. I have had many

locals tell me that, for a while, Batswana accepted anything

Europeans/Americans said because, “since it came from the white man, it had to

be better.” Luckily, that is

changing. But it is a past that I am

conscious of. I know that Peace Corps is

different. I know that Peace Corps

volunteers are not just white. We have

volunteers that comprise all races, sexualities and backgrounds. I also know that we are here to help the

communities do things themselves. But I

was still slightly uncomfortable with the “photo op” of the white woman helping

all of the poor, African children. It is

a theme we see time and time again in the news, cinema…everywhere. The well-off, middle-class, white person goes

in the hood and inspires all of the black thugs. It is a motif I strongly dislike.

So where do I fit into it?

“For Whites Only” made me realize something truly beautiful. The world may define me as a single, white

female, but that doesn’t mean I must do the same. I want to help those who need it—regardless

of race. And if that is in the black

community in the United States, so be it.

If it is in white suburbia, so be it.

I don’t need to define myself based on the color of my skin. Obviously it is part of me and has helped to

shape who I am but not any more than all the other events and experiences in my

upbringing.

I can define myself as white. American. Woman. Westerner.

Rhode Islander. But I can also say that

I love music, I love to dance, I love to swim, I love to read. And then how different am I from Batswana? I want to stop looking at the differences and

start looking at the similarities. There

is a lot more that unites us than divides us.

We have the most important thing in common. We’re human.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)